I wasn't sure where to put the odds-n-ends until I noticed I'd scribbled a list of em under the heading 'Odds-n-Ends', without really meaning it – why didn't I think of that? I thought – so here's a page called Odds-n-Ends containing odds-n-ends

A Mow Cop Diary, 1969

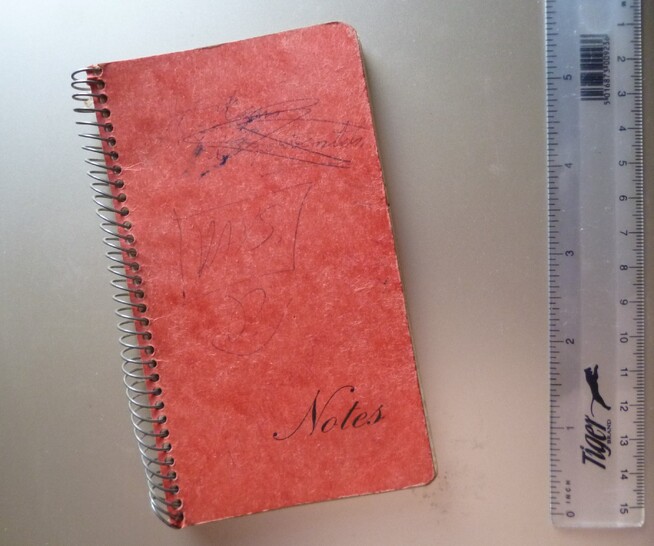

a few years back I came across a couple of small pocket notebooks I'd used in the early days of my local history research, and was surprised (and amused) to be reminded of a sort of diary I'd kept, starting at the age of 14¾, but a diary not (as might be expected) of my personal life and musings and miseries, like famous diarists such as Adrian Mole, but of events in the village of Mow Cop, with special reference to bad weather, power cuts, parked cars, and Pentecostals ... this is a transcript, together with introductory explanation and commentary

to view as a pdf in a new tab please click below

Tony's 400th Birthday (B)Log

this droll effusion was written for the Museum's web site in 2014 (and eventually, after some weeks of baffled or embarrassed headscratching, I imagine, was actually published there), on the 34th anniversary of my appointment and just days before my 60th birthday (which I conspicuously avoid mentioning – or should that be avoid conspicuously?), ostensibly to promote an exhibition marking the 400th anniversary of the invention of logarithms; it's copied here from my original draft, though the differences are only slight; the version on the Museum's web site is accompanied by a photo of an actual real genuine decimal point used by Babbage!

Tony’s 400th Birthday (B)Log

I have to declare a lack-of-interest – I failed my maths O level ...

I’d found myself at grammar school, doubtless due to some clerical error, I kid you not I was such a numbskull I was mystified why gardening wasn’t on the curriculum (it was the main subject at primary school on Mow Cop!) – and then later, having failed the necessary O levels, and been rejected by Leicester University, I ended up, doubtless due to another clerical error, at Oxford, where maths O level is, or was then, a compulsary entrance requirement; and then that summer’s day in 1980 when I came back to Oxford for a day-trip, the interview was just an excuse really, it never crossed my mind I’d get the job – I don’t suppose I told them about failing the maths O level but I did bring along some poetry magazines in which my poems had been published (I failed English literature O level as well), and handed them round to the interviewers to underline my un-suitability ...

cunning plan? not – they wanted me so badly that even though I didn’t have a phone they searched telephone directories (as they were called in those days) for anyone with the same surname at Mow Cop and as a result my father came to my house the very next morning and said he’d been woken up by a phone call from someone who talked posh asking if he was any relation to Tony Simcock, if so could he get a message to me to Phone Oxford Urgently – I suppose Superman feels like that, when the call comes, and like Superman I dashed to the nearest phone box (as they were called in those days) ...

so anyway, I was saying about my lack-of-interest in maths – it was a mixed compliment, they’d ended up (the job interviewers that is) having to choose between an astrophysicist and a poet (their own words) – job interviewers are always looking for someone dynamic and motivated and similar job-advert jargon, plus some knowledge of the subject would be an advantage (actually it said ability to type would be an advantage, to give you an idea how the world’s changed in just 34 years, now even my cat can do it) – but they weren’t, the interviewers weren’t remotely looking for someone motivated and with a maths O level, the astrophysicist scared the asteroids out of them he was so dynamic, they were looking for a docile simpleton so utterly lacking in interest and motivation that he (or she – as you have to say now) would stay in the job for decades ...

either that or it was another of these clerical errors; so anyway – today (August 18th, 2014) is the 34th anniversary of my appointment to the staff of the Museum – I don’t need a maths O level to work out the beautiful cosmic significance of the number 34 – and it’s a Monday as well – so that’s how I came from being a little boy so brainless he was allowed to skip lessons and do gardening, via being a temporary poet (I gave up poems once I’d got the job, of course, like you do), to helping Jennifer put on a small display of books and slide rules to commemorate the 400th birthday of Napier’s invention of logarithms – just between you and me what I really wanted to be was a comedian, but I settled for wanting to be a museum curator as the next best thing ...

I realise I’ve rambled a little – but what I was going to say actually was that I always felt like the chap in Jake Thackray’s song: “I used to think that logarithms were things that scuttle about in attics” (I can hardly believe Olivia’s never heard of Jake Thackray!); and then there’s Napier’s even zanier invention, the decimal point, can’t you just picture it? – a birthday display of decimal points – and all the puns you could get in? (what would you say is the Point of this exhibition? can you Point out a couple of the highlights? well, Kirsty, here’s a decimal point that was used by Babbage ...) I know I’m supposed to be lauding logarithms blaa blaa, but – a world without decimal points – we’d all be using sixteenths and you wouldn’t know whether you’d written a cheque for 4 guineas or 400 – and anyway, if there wasn’t a decimal point how would they know if I’d passed or failed?

TS

Editor’s note: We asked our archivist to write us a blog on how he and librarian Jennifer came to put together the current small display of books and slide rules that marks the 400th anniversary of the invention of logarithms, and this is what we got!

just in case it should be suspected that I took the exhibition's theme lightly, clicking the button will take you to the really serious labels for my part of the display

Joseph Wright

and while we're on blogs-n-things written for the Museum, here's one produced in connection with the 'Eccentricity' exhibition of 2011; a rich parallel blogiverse accompanied this exhibition, but it's hard to find it on the Museum's web site, where the blog archive only goes back to 2012; I hope it's not been junked, as this biographical piece on Wright is the only one I have my original draft of – and you'll see why I kept a copy if you read on

Joseph Wright and his Phonograph

Joseph Wright (1855-1930) was one of the most extraordinary people ever to rise to eminence in the academic world. For he was born in utter poverty, worked from the age of six (as a donkey boy in a stone quarry), and remained illiterate until he taught himself to read and write as a teenager. His thirst for education and love of language drove him forward; he studied at the

university of Heidelberg, supporting himself as a mathematics teacher; but it was his genius for languages that got him noticed. In 1891 he was invited to be Deputy Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford, and succeeded as Professor in 1901.

The achievement for which he is best remembered is the English Dialect Dictionary, a monumental six-volume compilation of regional words and expressions, published between 1896 and 1905. The project had been commenced under the medieval philologist Walter W. Skeat, but had proved prohibitively large and ambitious. Wright was undaunted by it, and when the University Press refused to subsidise it he paid for it to be printed from his own pocket, supplemented by a small number of subscriptions.

Yorkshire dialect was his true native speech, and for all his great learning he enjoyed speaking it not, as educated people often do, from amusement but because he believed passionately that dialects were respectable languages in their own right. He proved it by writing a learned phonetic grammar of West Yorkshire dialect, which his colleagues at first thought was a practical joke. He also published grammars of German, Old English, Gothic, and Greek. These have perhaps been superseded. But the English Dialect Dictionary is still, a century later, an essential and greatly respected reference book for scholars of language, folklore, and English social history.

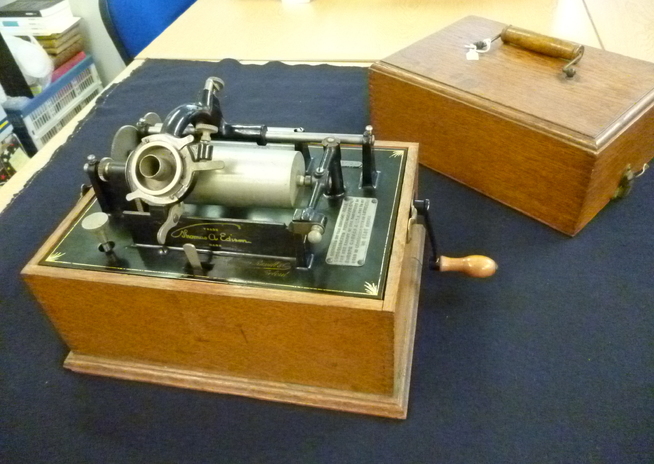

In addition to the usual lexicographer’s procedure of writing words and their details on to slips of paper (estimated at two million), Wright employed the most advanced technique available at the time – the phonograph. The early cylinder machines recorded as well as playing back, and the twelve wax cylinders accompanying Wright’s phonograph contain field recordings of English and Scottish dialect made by Wright and Sir William Craigie in 1900 and 1902. They are among the earliest recordings made of the voices of ordinary human beings.

The phonograph and the blank cylinders were purchased from James Russell & Co., the Oxford music shop (precursor of Russell Acott, which closed down this year [2011] after 200 years). They were given to the Museum in 1937 in memory of Wright by his widow Mrs Elizabeth Wright, who had heard that the Museum – which had recently acquired an original Edison prototype – was searching for an ordinary Edison-Bell cylinder phonograph to complete its display. In one sense it is – it is the ordinary standard Edison-Bell model of about 1900; but museum exhibits are not just what they are, they are what they have become through their association and history – and in that sense Joseph Wright’s phonograph is no ordinary phonograph at all.

History of Photography

history of photography doesn't really deserve to be relegated to the odds-n-ends, so it isn't; it starts with my little article about "The Beginnings of Photography in Oxford", one of the things I wrote in connection with the 150th anniversary of the invention in 1989

to go to this page please click below

or to read a poem about the invention of photography instead

Peter Drinkwater

my obituary of this eccentric genius definitely belongs among the odds-n-ends; Peter Drinkwater (1947-2013) – 'learnèd in esoteric subjects and with a long forked beard' – was an authority on the geometrical construction of sundials and an advocate of the teaching of 'dialling' – by the age of ten, he thought, even if you haven't quite by the age of eight, you should have grasped the mathematics, geometry and astronomy needed to design a sundial; he was also very fond of rabbits

to read the obituary please click below

Eccentricity Afterword(s)

speaking (as I was above, under Joseph Wright) of the blogs that accompanied the 'Eccentricity' exhibition of 2011, of which I was joint curator with Jim Bennett, this was the last one (blog I mean); a contribution by a guest speaker was poised by default to be the last, though it wasn't about the exhibition, so I made my mind up to give the exhibition itself the last word; and like the exhibition itself, where the ridiculous kept turning out to be serious etc (as described), this mock interview meant as comedy found itself broaching profound themes inherent in or raised by the exhibition; hence it was the perfect final word; with thanks to Laura for being a good sport and also doing some judicious censorship

Afterword(s) — Laura Ashby chats with “Eccentricity” co-curator Tony Simcock

Laura: So Tony, what’s it all about, eccentricity?

Tony: D’you mean eccentricity or “Eccentricity”?

L: Take your pick.

T: Well Laura, eccentricity turns out to be a bit like “Eccentricity” – or vice versa – when you see it it’s obvious what it is, when you describe it it’s a bit less clear, when you try to define it it goes all mushy. It slips right through your fingers.

L: Try anyway.

T: I’ll tell you one characteristic, that keeps cropping up. You must have noticed how it keeps swinging between poignance and panto …

L: I have indeed. But you’d better explain what you mean anyway.

T: You laugh and then you cry. You’ve no sooner convinced yourself that something’s completely ridiculous than you realise it’s saved the world. It’s the very opposite, it’s undiculous.

L: You’re not allowed to make words up, by the way.

T: Take Joseph Wright for instance. We introduced him in an amusing way – must have been a practical joke, bringing this chap with a broad Yorkshire accent to teach philology at Oxford. And accepting him because he was a great pipe smoker. But before long we had a lump in the throat – at least I hope we did …

L: I couldn’t swallow for a fortnight.

T: Picturing a man who started his career aged 6 as a donkey boy in a quarry, rising to become an Oxford professor and one of the most eminent linguistic scholars of his day. We note how Jevons’s logical piano was ridiculed, and, like Babbage’s difference and analytical engines, was a complete failure … then we remind ourselves that they are the forerunners of the computer, which means that the men who thought of these ideas and were once figures of ridicule must now rank as founders of the modern world. We make mild fun of dear old Lewis Carroll’s system of logic and the idea that it can be worked out as an equation in algebra; but that’s part of what modern computers do do.

L: Dee-doo do dee-doo.

T: And ravenous old Buckland, with his panther pie and mouse in batter, was the geologist who founded the subject of ecology – the study of living things with reference to their environment – and pushed back the boundaries of creation beyond the old wisdom of 4004 BC, ready for Darwin to step in with millions of years of evolution. So. Are they geniuses or nutcases?

L: Or, are geniuses all a tad eccentric?

T: OR – is eccentricity necessary, like curiosity and memory and oxygen? Necessary to big-brained bipeds, necessary to human intellectual progress, and thus to evolution a million years back and to science in recent centuries.

L: Cool – this is getting …

T: I know, you thought you were interviewing Edna Everage and you got Jonathan Miller instead.

L: Who?

T: The whole exhibition’s been like that. And that’s what I mean. The moment you see how ridiculous something is, it turns serious. The moment you think you’ve spotted a bit of pure eccentricity, you realise there’s method in the madness. Take Daubeny’s monkeys …

L: No thanks.

T: Even though he was ridiculously short and bespectacled and obviously had a very squeaky voice, Daubeny had a serious philosophy that science or anyway science teaching or anyway science teaching in Oxford or anyway science teaching in Oxford colleges …

L: [the look says it all]

T: Or anyway science teaching at Magdalen College, should be comprehensive and broadly based; so although he was a chemist and botanist himself, he introduced physics and meteorology and zoology – that’s the monkeys – and astronomy and geology etc into his teaching. He installed a big telescope at the Botanic Garden – you’ll probably say he was looking for life on other PLANTS!

L: I was going to say, looking for plant-life in space.

T: Mmm, better leave the jokes to me then.

L: Arumph.

T: But monkeys in a cage are a lot funnier than telescopes …

L: Especially when they escape …

T: But you see Daubeny’s monkeys and telescope were doing the same thing – they were expanding the curriculum.

L: No, you’ll never make expanding the curriculum seem funny.

T: That’s it. And several of our lecturers have bravely tried to define eccentricity or an eccentric, and its place in society or in science. It’s a tough assignment. Brian Regal’s conclusion that science and the world NEEDS people who waste their lives in quest of the non-existent Abominable Snowman is sort of sad, perhaps, more than funny. For that’s the point where eccentricity evaporates, or slips through your fingers.

L: Like old Bigfoot himself.

T: And you know Laura, it’s been doing this throughout the exhibition. You think you see it, shadowyly, on the hillside – you focus in – and it’s gone. Puff! It’s a puff of snow blown off the horizon by a distant breeze.

L: So it gets us nowhere?

T: Ah but we never intended – I don’t think we did anyway – to raise a debate about the nature of BEING a scientist or of intellectual evolution or of scientific discovery. Yet there it was, a big hairy footprint in the snow, a profound debate about these things appears to exist. We didn’t really intend to make fun of our heroes and heroines. Yet there they were, as soon as our backs were turned, pulling funny faces at us …

L: Or farting.

T: Laughter’s extremely good for the brain by the way.

L: Save me a bottle.

T: And I’m sure we didn’t intend the exhibition to be about eccentricity.

L: What was it meant to be about then?

T: I’m glad you asked me that. Because there IS something that’s hardly been raised at all, something absolutely fundamental, and it’s got nothing or little to do with eccentricity, and almost – almost – tempts me to say that everyone’s missed the point. But I won’t say that …

L: Oh go on.

T: Because every point of view is valid, and indeed a characteristic of something’s worth is its depth – its capability of accommodating multiple levels of meaning or relevance. It’s only, well, for my part, I wish that more people who came around museums were interested in MUSEUMS … You’ll say, what an odd thing to say …

L: What an odd thing to say, Tony!

T: After visitors have poured into our lovely museum and enjoyed and learned from the collections they’ve seen displayed there. But to me the exhibition “Eccentricity” is about the scope and parameters of museum collections. And there’s a big debate there. And we haven’t had it, and we can’t have it now …

L: Oh let’s …

T: No, it’s too big and boring. And d’you know something – it’s probably a good job nobody’s thought of it. Because it’s a debate that could go against us. Nowadays, museums have to write mission statements and collecting policies and even disposal policies. And donors have to sign legal transfer documents. And safety officers have to run geiger-counters over things.

L: [raised eyebrows]

T: No, honestly, Soddy’s suitcase was geiger-countered before we put it on display.

L: Get to the point.

T: Hardly anything in the exhibition would be acquired today under today’s collecting policies. Several things came quite accidentally. Burdon Sanderson’s wallet was swept up with miscellanous stuff from the floor of Haldane’s laboratory and bunged in a tea-chest to be sorted out 20 years later. One of the things in the tea-chest was a stale sandwich, which I threw away.

L: Yes, we’ve got that joke somewhere else.

T: It’s no joke Laura. Neither our collecting policy nor our disposal policy says anything about sandwiches or suitcases. Did you know we’ve got King Charles II’s address book?

L: Throw it away!

T: And the world’s oldest collection of birds’ eggs.

L: So why aren’t they in the exhibition?

T: And a melted tile from Hiroshima …

L: Cool.

T: From panto to poignance. I wonder whether there shouldn’t be a regular, changing exhibit of an unexpected offbeat treasure from the collections. Because you see I think – and I’m not sure eccentricity was the best word for it – the exhibition was about …

L: The exhibition called “Eccentricity”.

T: Yes. I sort of suspect the exhibition was about the nature of a museum collection. The debate – no, we’ve decided it’s best not to encourage a debate – the generality, the paradigm, the background noise, the footprint in the snow isn’t to do with the eccentricity of historical characters, neither eccentric like nutty nor eccentric like outside the mainstream. It’s to do with eccentricity in serious museum collections. The frilly peripheries of the collections. The crimping machines. The Chinese typewriters. The items in the collection that are way off centre, that don’t conform – nonconformity would have been a better word …

L: That would have pulled the crowds.

T: The things in the collection that don’t conform to any conceivable definition of what we’re about or what we collect AND YET ARE TREASURES EVEN SO. Put that in capital letters.

L: I shall.

T: Poignant treasures. Revealing treasures. Entertaining treasures. Informative treasures. Important treasures even so.

L: Priceless.

T: Yes, get that word in somehow too. But they’re waifs, they’re all orphans and foundlings, they’re the most fragile parts of the collection. Fragile in terms of the probability of them ever having been saved in a museum at all. Several of the objects in the exhibition we’ve had for decades, but I’ve catalogued them only recently – elevating them to the status of real museum objects. Who was it who said ‘museum objects aren’t just what they are, they are what they’ve become’?

L: You I think.

T: Well there you are then. Soddy’s suitcase is one – an object I elevated from statuslessness I mean – Miss Willmott’s empty lantern-slide box with her name plaque another. Wonderful paradox there – Soddy’s suitcase had no identity as a museum object in its own right because it was just a container, a cardboard box manquee …

L: Can we say substitute?

T: Just a container – it was full of lantern slides. Miss Willmott’s lantern-slide box had no identity as a museum object in its own right because it was empty, it had no lantern slides in it. I like that paradox.

L: Worthless if you’re full of lantern slides and worthless if you’re empty.

T: D’you see what I mean though?

L: Not the faintest.

T: It’s the museum world turned upside-down. The exhibition is SUBVERSIVE. It’s nonconformist. It’s an exhibition curated by levellers. It’s revolutionary. The collection’s most worthless, improbable, unregarded, off-beam, accidental, ex—I nearly said eccentric!

L: Not allowed, miss a turn.

T: Most peripheral most waif-like objects, dusted down and displayed as a collection of priceless fascinating treasures. And it works!

L: Worked.

T: It worked. They are! They’re priceless.

L: They are indeed. Well I’m sorry we’ve run out of time now, so thanks a lot Tony.

T: Thankyou Laura. Byebye.

L: Byeee … Now he’s gone I should just add that Tony Simcock’s opinions are not necessarily the opinions or policies of the Museum of the History of Science or of Oxford University. To be honest – I suspect he’s a little eccentric …

Museum Under Review

this infamous polemic from 1993 I nicknamed at the time my 'suicide note', since an attack on my employer (I mean the University of Oxford), albeit written in impassioned defence of the institution I worked for (the Museum), could hardly be construed as less than professional suicide; I didn't get sacked, not least because nobody really gave a damn, and some puny david shooting off a pebble doesn't bother a hard-arsed monster like the university; my main thought on reading it again after all these years was relief that I'd included reference to 'lavatories' – notwithstanding which, it may still qualify as the least funny thing I've ever written!

to open as a pdf in a new tab please click the button