I didn't particularly intend the history of science to be represented on this web site, unless amongst the odds-n-ends – but then again, being already a cupboardful of incongruities how could I justify shooing the joker in the pack? and anyway the so-and-so claimed 36 years of my life, quite a long time to be distracted from one's true mission; so I suppose I should chuck into the stew a few of the things I've written over those years in this subject area; for an entirely honest account of how I got catapulted into it from a state of scientific numbskullery see my 400th birthday thingamyjig

no topic within the broad remit of history of science (and the even broader one of museums thereof) is a more suitable starting point than my old friend Regiomontanus, whom I've toyed with on several occasions, and who stands at the fountain-head of the evolution of modern science

Regiomontanus:

The Man in the Moon

among blogs-n-things written for the Museum's web site over the years, this nice little piece from 2015 promotes my long-cherished idea that the face in the moon at the centre of a lunar volvelle in the 1482 edition of Regiomontanus's calendar should be interpreted as an authentic portrait of the man himself – not least on the grounds that no one would would give the man in the moon such a bumpy nose

Regiomontanus: The Man in the Moon

By Tony Simcock, Museum archivist

Here is one of the Museum’s oldest books. Indeed, it is one of the first and most influential scientific books ever printed. It is the 1482 astronomical calendar compiled by Johannes de Monte Regio – his name can be seen at the end of the first and beginning of the second lines of the title-page (if it can be called that – title-pages hadn’t really been invented yet). Posterity knows the author as Regiomontanus, and honours him as one of the founders of the scientific renaissance – the dramatic revival of scientific learning and curiosity at the end of the Middle Ages.

Central disc of a lunar volvelle in the 1482 astronomical calendar of Regiomontanus, at its centre a distinctively realistic profile face in a crescent moon – evidently the author himself, who had recently died when this edition was printed

(book illustrated courtesy of the History of Science Museum, Univerity of Oxford)

We tend to think of the ‘Man in the Moon’ as a face occupying the Moon’s disc, though in earlier folklore he was imagined as a full-length figure, perhaps a little hunched and chilly, accompanied by a dog and a bush, or bunch of twigs. He is ‘yonder peasant’ whom King Wenceslas noticed gathering firewood in the snow. Shakespeare describes him similarly in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (about 1595):

This man, with lanthorn, dog, and bush of thorn,

Presenteth Moonshine.

That’s what people gazing at the full Moon at that period made of the various dark shapes.

One un-typical early face in the Moon, however, represents something more than either folklore or optical illusion. Modelled into a crescent moon at the centre of a lunar volvelle in our 1482 book is a realistic profile face with distinctively rugged nose. It seems to be an authentic contemporary portrait of Regiomontanus himself, who had recently died at the early age of 40.

This posthumous edition of his astronomical calendar was printed in Venice by Erhard Ratdolt, a great admirer of Regiomontanus and himself a pioneer of scientific printing and illustration. The first edition of the work had been issued at Nuremberg where, in about 1470, Regiomontanus set up a printing and publishing business, as well as an instrument making workshop. He was the first publisher of astronomical books. His vision was not one of cloistered scholarship for a learned élite – he set out to use the recently-invented printing press to disseminate mathematical and astronomical knowledge, and to make instruments for calculation and time-telling more widely available. Four real instruments, but printed on thick paper rather than expensively engraved in metal, are included at the end of his book.

It was thus much more than just a calendar; it was a compendium of astronomical and mathematical information with an overtly practical and educational purpose. It includes charts for daylight hours, phases of the Moon, and dates of Easter, with an explanatory essay, and an innovative calendar of predicted solar and lunar eclipses down to 1530. The pages providing an at-a-glance eclipse calendar by means of diagrammatic pictures of total and partial eclipses seem an obvious idea now, but it was the first time this simple visual technique had been used.

Study of the Moon may have had a long way still to go, but the Regiomontanus calendars were a giant leap in the direction of modern scientific knowledge. How appropriate that Ratdolt should add this touching tribute to his mentor in the 1482 reprint, and in so doing bequeath us a uniquely down-to-earth take on the Man in the Moon.

Regiomontanus and the Sphere of Destiny

another article about our old friend coming shortly

nezco mujinxgilla akngrnare aingilla alkeos yrtecenas nijgstxm ipsuorxor sihxmezzg mutlitnec lekdcxgilla agtyfringilla axslkcens

History of Photography

history of photography doesn't really belong under the history of science, even though technically it's a scientific invention; anyway, it starts with my little article about "The Beginnings of Photography in Oxford", one of the things I wrote in connection with the 150th anniversary of the invention in 1989

to go to this page please click below

Peter Drinkwater

Peter Drinkwater (1947-2013) was an authority on the geometrical construction of sundials and an advocate of the teaching of 'dialling' – by the age of ten, he thought, you should have grasped the mathematics, geometry and astronomy needed to design a sundial; he was also very fond of rabbits

to read my obituary of this eccentric genius please click below

Foucault's Pendulum in Oxford

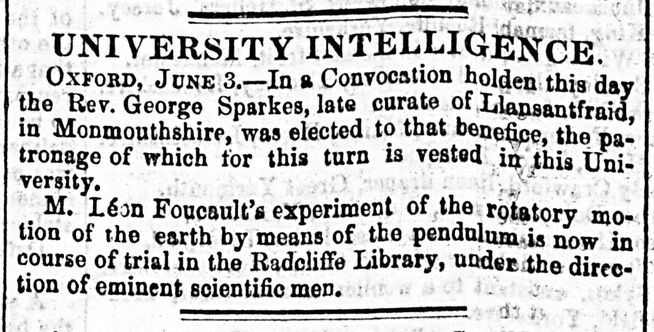

after writing the entry for Robert Walker, an unjustly neglected Oxford physics professor, for the Dictionary of National Biography (Missing Persons volume, 1993), I drafted a note (that's academic-speak for an article too piddling to deserve the name) about one of his more ambitious experimental demonstrations; that there'd been a huge, spectacular Foucault's pendulum in Oxford like the famous one at the Panthéon in Paris seems to be one of Oxford science's best-kept secrets, never mind that it was also one of the earliest; as often happened, my article was never finished or published, meaning that in returning to it now I've been able to amplify it considerably

‘That Beautiful Experiment’:

Foucault’s Pendulum in Oxford

The famous experiment of Foucault’s pendulum is that rare thing, a scientific experiment that not only caught the popular imagination but became – and remains after more than a century and a half – a popular public spectacle. The original experiment needed a reasonably long pendulum for the required effect to be convincingly observed and accurately measured; to be visibly demonstrated to an audience a very long pendulum hung in a very tall space combined breathtaking spectacle with a powerful lesson in physics and cosmology .....

From The Sun, Wednesday evening, June 4, 1851, p.11

coming soonish - honest - just needs a bit of twiddling!

Reason's Dim Telescope

an unexpected contribution to the history of science arose during my studies of Staffordshire poets, when I found myself reading a poetic tirade against one of science’s favourite heroes, Joseph Priestley, and in fact against science itself, intruded into a volume of poems that the nice, inoffensive Staffordshire poet Priscilla Pointon (Mrs Pickering) shared with two other contributors, one being the nasty and thoroughly offensive Birmingham rabble rouser John Morfitt; my short article about it was published in the distinguished history of science journal Notes and Records of the Royal Society in 1995, edited at that time by Desmond King-Hele, biographer of Erasmus Darwin, who thus needed no pursuading (his only editorial suggestion being that I add more refs to him in the footnotes!)

to view as a pdf in a new tab please click the button

>>> return to top of page <<<